From Illicit Stills to Global Success

There are few things more synonymous with Scotland than whisky and with around half of the country’s single malt distilleries operating in Speyside, it’s safe to say that this is the heart of the industry. Thanks to the fertile glens and crystal-clear waters, Scotland’s national drink has been an integral part of life here for hundreds of years.

Today that’s evident from dozens of large distilleries that dominate the towns around Moray. However, travel back just 200 years and the Speyside whisky industry was a very different beast. Instead of a highly prized, sophisticated dram this was illicit liquor, distilled in secret and smuggled by a network of enterprising people through various elaborate means.

Popularity on the Rise

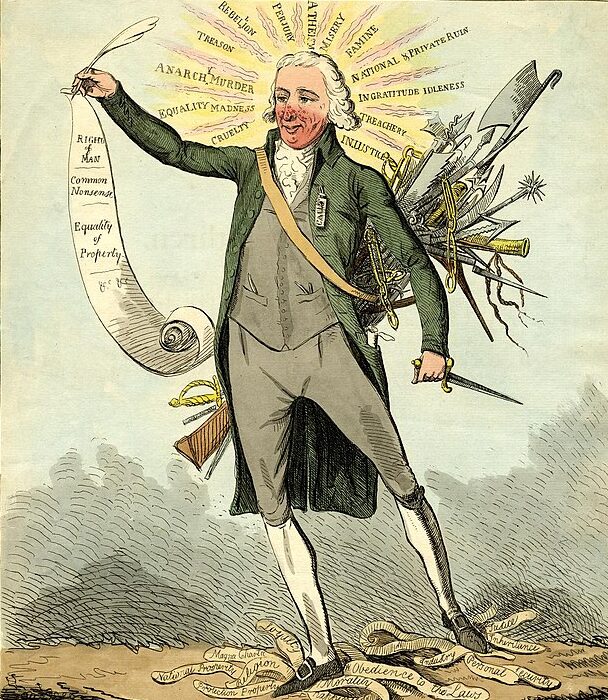

In the 17th century, the popularity of whisky was increasing, and the government saw an opportunity to cash in. Taxes were first introduced on spirit for sale in 1644, however production for personal use was still exempt. As time went on, the rules got stricter, and the duty got higher until eventually, home distillation was banned entirely.

Unperturbed by this new law, these small-scale distillers took their business underground, sometimes literally.

For most industries, the sheer inaccessibility of the wild hills around Speyside would be a hindrance however, for these industry pioneers, the harder it was to reach them the better. Most of the operations took place safely hidden in the wilderness, far away from well-trodden paths and making use of the many available sources of running water. Some stills were so well hidden that their remains are only just being discovered today.

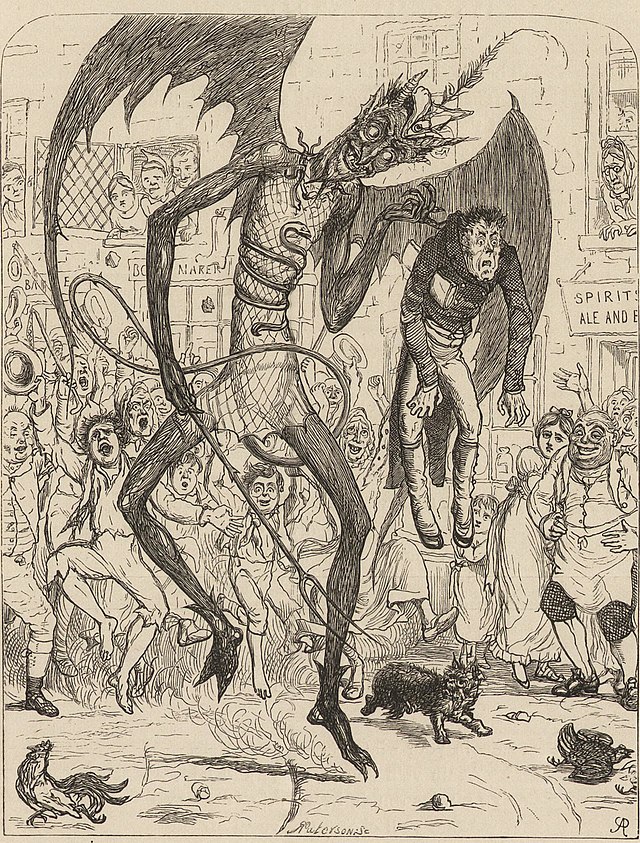

Illicit stills were appearing in their thousands and government officials known as excisemen or gaugers were employed to hunt them down. Unfortunately for them, they were operating in an unfamiliar area, badly outnumbered and very often outwitted.

The Excisemen

By the 19th century, it was clear that the excisemen were fighting a losing battle with 14,000 reports of illicit distilling in one year alone. Where punishment had failed, maybe enticement would succeed, and the government decided to make legally distilling whisky a much more accessible and profitable industry.

The 1823 Excise Act came into force, easing the restrictions on licensed distilleries and things began to change. 10 years later reports of illicit stills had already dropped to less than 700. Poachers turned gamekeepers and the entrepreneurial characters who had honed their skills on the black market went on to found some of the most recognisable names in Scotch Whisky.

Not everybody carried out their illegal endeavours in the isolated hillsides, some were bold enough to manage operations from their home. It was a risky business and these illicit stillers had to get a little more inventive to avoid detection. Often that was left to the women of the house, watching the still along with the children and there are stories of whisky deliveries being hidden under dresses or inside fake pregnancy bumps.

Helen Cumming, the Backbone of Cardhu

The most famous story of illicit distilling is a legendary tale of deception and cunning which forms the backbone of Cardhu Distillery. Helen Cumming and her husband John ran a small farm at Cardow, high in the hills above the River Spey. While John spent his time toiling in the fields, Helen was responsible for the family’s other, less legitimate business venture.

Like so many others around Speyside, Helen distilled and sold her homemade whisky to help make ends meet. The farm was under constant threat of unannounced visits by the dreaded excisemen, but they were no match for this wily businesswoman. She came up with a clever plan to deal with her unwanted visitors, while also lending a helping hand to her neighbours.

She made sure that whenever the still was running, there was fresh bread ready to bake in the oven to explain the yeasty smell of fermentation.

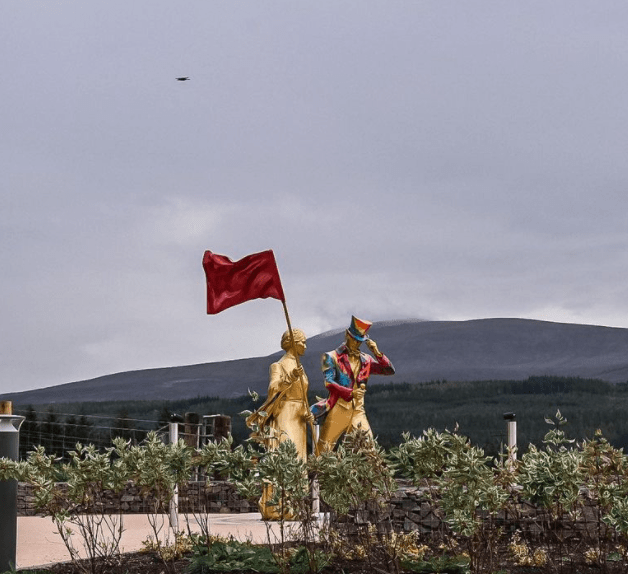

If the excisemen did arrive then with a warm smile and a pinny covered in flour, Helen invited them in to taste her fresh bread, before sneaking out the back and raising a red flag up high. Everybody else in the community knew exactly what that signalled, giving them enough time to pack up their illicit stills and hide all evidence.

The Cummings knew that whisky was their future and were one of the first to go straight with a distillery license in 1824. Cardhu carried on its tradition of a strong female presence when operations were taken over by Helen’s daughter-in-law Elizabeth. She built on her mentor’s foundations, greatly expanding operations, and building huge new warehouses that are still standing today.

The superior spirit that she helped to produce soon became a favourite of expert blenders including John Walker & Sons. In the late 19th Century, Johnnie Walker took such a serious interest in Elizabeth’s business that they decided to buy it. She wasn’t about to abandon all the hard work that she and Helen had put in though. Elizabeth ensured that the family would continue to run the distillery, the workers were kept on and her son John Cumming was given a seat on Johnnie Walker’s board.

Helen’s Legacy

Women continue to shine in the world of Speyside whisky, an industry that was once sadly considered to be a man’s world or to be producing a masculine drink. Cardhu’s current distillery manager Roselyn Thomson and Macallan’s master whisky maker Kirsteen Campbell are just two names amongst many.

This should by no means be a shocking revelation. We have trailblazing historical characters like Helen Cummings to show that women have been involved in whisky from its earliest days. The male-dominated era that came later is now thankfully fading away again.

Speyside whisky has come a long way from those tiny stills nestled amongst the heather or hidden in farmhouse cupboards. This internationally renowned spirit is now rightfully celebrated around the world, but things may have been very different if the excisemen had won their battle against the illicit stillers. Maybe we should all raise our next dram to their tenacity in risking the wrath of the authorities, and ultimately giving us the Speyside whisky that we enjoy today.