The Bravest Men on the Spey

Scotland was once covered in trees. The Great Caledonian Forest was so widespread that a squirrel could leap all the way from Forres to the peaks of the Cairngorms without ever touching the ground. As human settlements and farmland spread, the woodland slowly retreated to just a few lucky places.

One of those spots still thick with forest was around the tributaries of the River Spey. Today the river is best known for producing incredible whisky and excellent salmon fishing, but not so long ago the Spey was host to a much more dangerous trade. Felled trees were making use of the fastest flowing river in Scotland, taking a rollercoaster ride all the way from the hills to the shore.

For hundreds of years, water had provided the most efficient form of travel. Roads were poorly made and dangerous, while railroads were restrictive and took a long time to spread. If somebody wanted to transport tons of heavy timber out of remote Scottish forests, they were going to need nature’s help.

Who were the Timmer Floaters?

All around the forests, trees were felled then stripped of branches before being dragged by horse to any tributary with enough water to carry it. Boys were employed to lead the horses, clearing fallen branches and obstacles out of the way. From there, the floating logs were guided towards the Spey by agile young men with hooked sticks. It was a race for them to keep up, running along the banks, over roots and rocks to ensure their cargo didn’t get tangled along the way.

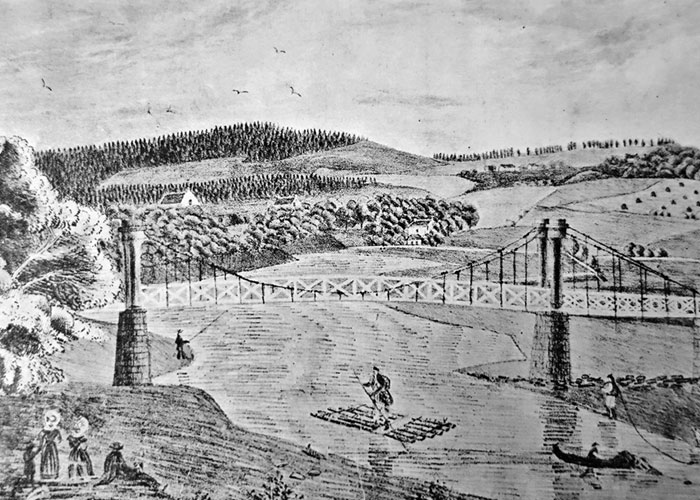

Initially, the same method was often used to move the prepared logs down to the coast at Garmouth for export. Hundreds were let loose at the same time to float on their own, chaperoned from dry land and caught before they could disappear out to sea. However, that much heavy timber out of control was a dangerous business. So much damage was caused to expensive bridges along the way that the authorities forced a change.

In 1813 the government passed a new act to ban any felled trees from floating under bridges unless they were tied into rafts and manned by a timber floater.

Tightly bundled together, these rafts were more like floating islands. The timber floater stood on top, ready to steer a safe passage down the precarious river with the help of a long, hooked pole called a floater’s cleek.

These were rough, burly men powered by oatmeal, bannocks and cheese. They had no waterproofs or waders and were instead rendered oblivious to the cold by copious amounts of coarse whisky. A young boy circulated a few times a day with a small cask on his back, handing out measures of liquid warmth.

It was a family business, and young boys would eventually graduate to guide their own raft one day. Floaters were trained to follow in their father’s footsteps, learning every inch of the river perfectly. Each individual rock, rapid and bend was ingrained in their minds and that expertise was invaluable for the steady supply of Speyside timber.

The Story of Mr Lobban

These men might have been highly skilled with years of experience, but they were still victims to the whims of the river and accidents happened. A man called Joseph Lobban recalled a story about his father on one of his many regular trips down the Spey in the late 19th century.

His raft had been caught on the rocks near Carron, becoming well and truly stuck. Out of the water, these rafts weighed tonnes, and it took him 3 hours to work it free again. By the time Mr Lobban and his shipment arrived at Garmouth, he had missed the last coach back upriver.

Rather than sit around waiting until the next day for another, he decided to walk the 40-mile journey home. All he carried was a little bag of oatmeal and he begged at the houses along the road for some hot water to make his brose. Lobban finally arrived back at his cottage around 6am, just in time for a quick breakfast before strolling down to the water to prepare the next raft.

The Speyside Timber Industry

Timber was floated down the Spey for generations, the first recorded commercial sale comes from the early 17th Century. When it came to shipbuilding, Speyside pine was considered the next best thing to oak which was becoming increasingly rare.

The floated timber made its way all around Britain, installed as railway sleepers or even bored and used as London waterpipes.

At first, the majority was simply prepared, loaded onto ships and exported. That all began to change in the 18th century. The Duke of Gordon sold thousands of trees from his vast estates to a pair of merchants from Kingston-on-Hull. Instead of just exporting the timber, they decided to use some of it themselves.

New shipbuilding yards were established at the mouth of the river and the village was named Kingston after their hometown. It’s not obvious today, but at one point there were at least seven separate shipyards in action around the Spey. Over the years, hundreds of ships of all sizes were built at Kingston, from wood rafted down the river by those remarkable timber floaters.

The End of Timber Floating

Unfortunately, Kingston’s unique selling point would also be its downfall. It had been in the perfect place to take advantage of thousands of trees felled all around Speyside, but wooden ships were going out of fashion. As the 19th century wore on, steel and steam began to take over and shipbuilding on the Spey slowly reduced.

With only small fishing boats to provide for, the role of the skilled timber floater decreased. A remarkable but little-known chapter in the history of Speyside had finally come to an end. The only rafters seen on the River Spey now are there purely for a thrill that was once part of the timber floater’s everyday life.