Separating Man from Myth

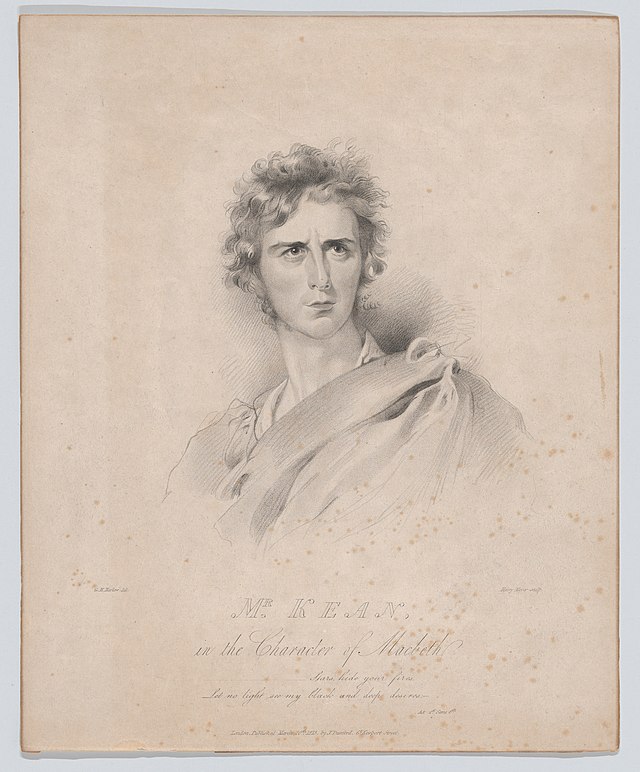

Known around the world as one of the most famous Kings of Scots, the name Macbeth instantly conjures up images of betrayal, murder, witchcraft and tragedy. While the name might be well recognised, many fans of William Shakespeare are surprised to discover that the star of his Scottish Play isn’t a fictional character, but a genuine 11th-century figure from Scotland’s turbulent history.

They may be even more surprised to learn the story behind the real Macbeth and how his impressive reign played out. Often the truth is even more exciting than fiction and this man from Moray might well be the most misunderstood monarch in history.

Portrayed by Shakespeare as a murderous usurper, the Thane of Glamis and Cawdor was quickly destroyed by his own ambition, only to die pitifully alone. While Macbeth was by no means a pacificist, he was no more violent than the next nobleman in medieval Scotland. He certainly wasn’t Thane of Glamis or Cawdor but instead held a much more powerful position, ruling over the largest region in Scotland as the Mormaer of Moray.

The King of Scots

In Macbeth’s day, the title “King of Scots” wasn’t automatically passed down directly from father to son. Since Kenneth Macalpine became King of Alba in 843, not a single son had succeeded his father by the time that Macbeth was crowned. For generations, even back into the Kingdoms of Picts and Dalriada, power had gone to the person who could prove that they deserved it or had the strength to take it.

That was equally true for the Mormaers of Moray, Macbeth’s father being murdered by his nephews who took control for themselves in 1020. Around 12 years later, one of those nephews Gille Coemgain found himself trapped inside a hall with his closest followers and burned to death. While we can’t prove that Macbeth had anything to do with it, he was the man to step forward, take control of Moray and marry the murdered man’s widow.

Duncan I King of Scots, the man Shakespeare accused Macbeth of murdering, was a poor leader who had been gifted the crown by his grandfather Malcolm rather than earning it. After being defeated in battle twice in quick succession, the leading Scottish nobles were quickly losing confidence in him. In an attempt to quell the grumblings in the north and to prove his ability as King, Duncan marched into Moray to face Macbeth.

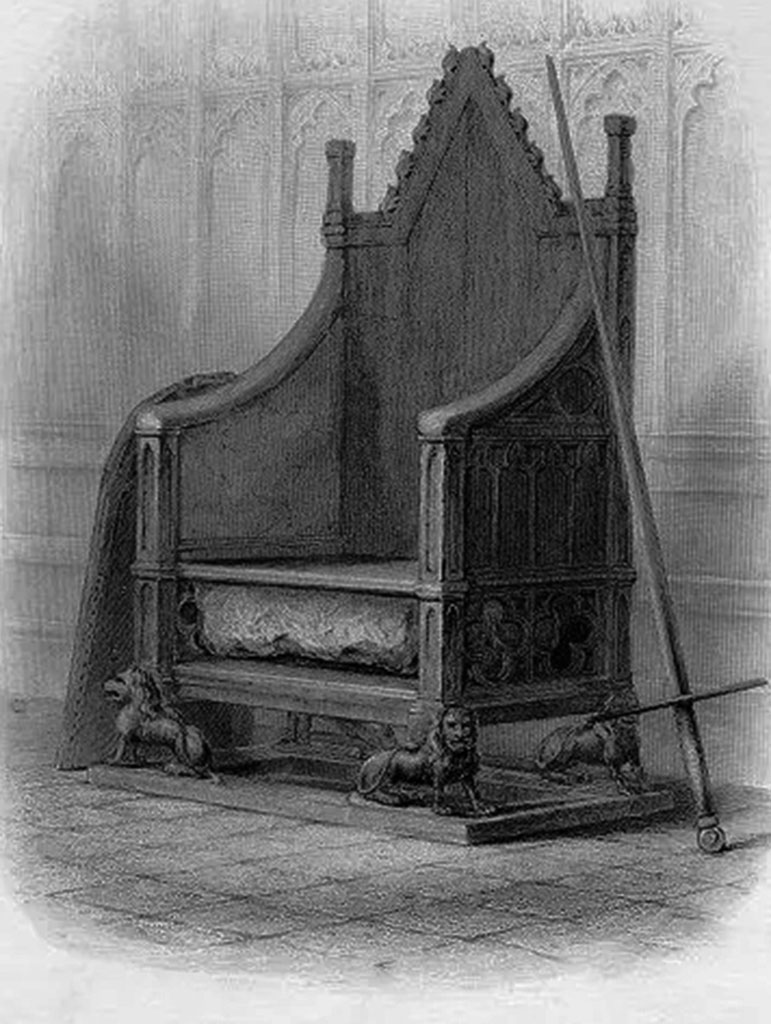

It proved to be a deadly mistake, with the royal army being crushed at the Battle of Pitgaveny near Elgin. Rather than being assassinated with a stealthy knife in the dark, Duncan was fatally wounded during an action that he himself had instigated. Macbeth was the obvious successor, quickly being declared the new King of Scots and subsequently crowned in Perthshire on the symbolic Stone of Scone.

The Rule of Macbeth

He was an effective King in a time of great pressure in Scotland, a country that looked very different than it does today. The Vikings had taken a firm grip on Shetland, Orkney and the Outer Hebrides, while the Kings of England were constantly threatening to push their border further north. While Scotland had technically been united for 200 years, the ancient Kingdoms of Strathclyde and Moray still saw themselves as semi-autonomous.

It required a strong hand to keep all of those different factions in check and that was what Scotland found in Macbeth. His secure position is emphasised by the fact that we know he travelled to Rome on pilgrimage, the first King of Scots to do so. That was an expensive journey which would have taken months, not something that a ruler struggling to keep hold of his nation could have afforded to do.

It’s said that while there, Macbeth scattered money to the poor like it was nothing more than seed. The King of Scots was clearly doing very well for himself and the rest of the world now had a chance to see it.

End of a Reign

Macbeth’s generally peaceful reign was too good to last and things began to come to an unavoidably bloody end. In 1054 a large army from Northumbria marched all the way to Dunsinane Hill to clash with the Scots. It was a truly bloody battle, with thousands of casualties which was an enormous death toll in an era of mostly small-scale conflicts.

Macbeth survived Dunsinane, but his personal authority had taken a large hit, forcing him to fall back on his traditional power base of Moray. Just a few years later Malcolm Canmore, the exiled son of King Duncan, gathered his own army, possibly with help from the Orcadian Vikings, to corner the King of Scots in Aberdeenshire.

The Battle of Lumphanan was the final act for Macbeth who ended his rule with a sword in his hand, just as he had started it.

Like those Kings who came before him, Macbeth’s body was taken from the mainland, on the long journey to the holy Isle of Iona off the west coast of Scotland. There, he was carried along the Street of the Dead to be put to rest in the Reilig Odhráin where he reputedly lies amongst sixty honoured Kings.

Macbeth was a tough man living in a tough time, a warrior King who defended his people and his borders when the need arose. He was also a capable leader, with a long and surprisingly uneventful reign who was done a disservice by a playwright almost 600 years after his time. This was no jumped-up tyrant who seized power for his own benefit before squandering it. The real Macbeth was a strong and wise ruler whom we can confidently call the last great Gaelic King of Scots.