Moray has been one of the most vitally important regions of Scotland since the nation’s earliest days.

Wedged between the dangerous heights of the Cairngorm Mountains in the south and the Moray Firth in the north, this passable stretch of countryside became a military highway. It’s no surprise then that the hills, glens and coastline of Moray have all seen more than their fair share of action over the centuries. From the Viking Age to the modern day, there are stories to discover from almost every major conflict in Scotland’s history.

Battle of Mortlach

Over 1000 years ago, the grounds of Mortlach Kirk in Dufftown are said to have witnessed a ferocious but obscure battle between the Scots and the Vikings. In the year 1010, a strong Scandinavian force gathered on the Moray coast and began steadily making its way deeper inland along the Spey.

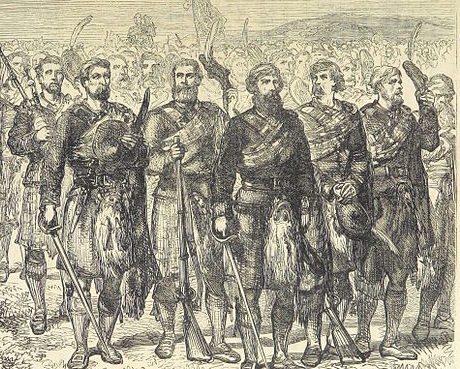

King Malcolm II rushed northwards to halt their progress, but his untrained army of farmers faced battle-hardened warriors. The Scots caught the invaders near the Dullan Water where it ran past a small chapel at Mortlach and full of enthusiasm, rushed to attack without any thought or battle plan.

The fighting was so intense that three of the Scottish leaders fell early on and King Malcolm was beginning to worry. He had been defeated by the Vikings before and if something didn’t change soon then this could mark the end of his reign. Turning to face the chapel on the mound above him, the King fell to his knees and prayed to St Moluag.

He vowed to transform the chapel into a cathedral if the Scots won the day and all of a sudden, the tide started to turn. The Scots began pushing their enemy back step by step and Malcolm re-joined the fray. Eventually, the Vikings broke ranks and began to flee, but the Scots kept on fighting. Malcolm himself was determined to bring down the Scandinavian leader Enetus, pulling him from his horse and brutally strangling the warrior with his own hands.

The King extended the chapel at Mortlach by 3 spear lengths, which was enough to keep his promise to St Moluag. This wouldn’t be the last time that Vikings would try their luck on the Scottish mainland, but they had learned to be wary of invading Moray.

Battle of Glenlivet

The late 16th century in Scotland struggled greatly with religious strife and violent struggles between the old Catholic order and the emerging Protestant regime. By 1594 laws restricting the Catholic faith were introduced by King James VI and it seemed inevitable that bloodshed would follow.

Influential nobles from the northeast gathered behind the Earls of Huntly and Errol in opposition to the King and a large army led by the loyal Earl of Argyll travelled north to deal with the rebels. As one side marched through Badenoch and Strathspey, the other moved west from Aberdeenshire. The natural meeting point would be Moray and result in the mostly forgotten Battle of Glenlivet.

The King’s force was 10,000 men strong but made up mostly of untrained militia and with an inexperienced 19-year-old Argyll in charge. Still, they were confident against Huntly’s much smaller force of around 2000, so were shocked to see them rushing to attack.

The rebels gambled that Argyll and his men would panic, advancing up the hill with cavalry and powerful field artillery in support.

Their confidence paid off when huge swathes of Argyll’s army abandoned the field without striking a single blow. The men who remained fought hard and Huntly was almost killed when his horse was shot out from under him. A few hours later and Argyll had suffered a crushing defeat, allegedly being led weeping from the field.

The rebel Earls may have won the day, but all they had really achieved was buying some time. King James himself soon led another royal army north and both Huntly and Errol had little choice but to flee the country.

Skirmish at Keith

Like many parts of Scotland, Moray played a part in the doomed Jacobite rising of 1745-6. Bonnie Prince Charlie’s force had retreated to Inverness, determined to hold the city at all costs. The Government army had set up their base in Aberdeen before marching north and west. Once again, Moray would be caught in the middle.

A month before the Battle of Culloden, a small detachment of around 100 Government soldiers led by Alexander Campbell entered the town of Keith. When word reached the Jacobite force at Fochabers, they sprung to action and immediately marched to engage. Rumours were circling that the main Government army was drawing closer, so the skirmish had to happen quickly.

Around 1000 Jacobites under Major Nicholas Glasgow accompanied by French Hussars reached Keith in the dead of night, prowling around the outskirts in the darkness. When challenged by a sentry, they simply replied that they were friends of the Campbells. Welcomed in, they quickly overpowered the unsuspecting guard and crept into the streets of Keith.

The Campbells put up stiff resistance, firing relentlessly from the kirk windows, but they were fighting a losing battle. Taken by surprise and badly outnumbered, they were merely delaying the inevitable. Eventually, the 80 remaining soldiers surrendered and were marched back to Fochabers as prisoners. The Skirmish at Keith would be one of the last small victories for the Jacobites.

Moray’s Modern Military History

The region’s important wartime role carried on into the modern age. Wander the beaches and forests along the Moray coast and you’ll be met with silent pillboxes and long strips of anti-tank blocks. This stretch was a potential invasion risk during WW2, but if Britain’s enemies wanted to land troops here, then they were going to have a fight on their hands.

Although they were never tested against European war machines, some of Moray’s defences are losing a very different kind of battle. The immense power of nature is taking its toll in places like Roseilse, where pillboxes sink into the sand and concrete cubes disintegrate against the elements.

Constructed in the same period, but in much better condition, RAF Lossiemouth is now the last operational air force base in Scotland. It carries on a proud tradition, representing Moray’s military might, with the region still defending Scotland to this day.