The early medieval people known as the Picts lived in northern Scotland for a period of about 600 years (from roughly AD 300 to AD 900) and left many traces in modern-day Moray, which lies in the heart of what once was Northern Pictland.

Burghead Fort

On the north Moray coast lie the remains of Northern Britain’s largest known early medieval promontory fort, a type of defensive structure located at the coast’s edge. Previously thought to have been built by the Romans or the Vikings, excavations at Burghead in the 1970s indicated that the site was actually a key royal and maritime Pictish power centre from the 6th – 10th centuries AD (around 1,400 – 1,000 years ago).

Kings and expert craftspeople visited and lived within the fort’s eight-metre-thick and six-metre-high rampart walls, which also housed an early Christian chapel and a very complex well, which can still be visited today. Experts think that the fort was destroyed in the 10th century AD, perhaps by Vikings or through internal conflict.

Sadly, a large portion of the fort’s remains (as well as dozens of iconic stone bull carvings) were demolished during the building of the modern town and harbour in the 19th century, and coastal erosion has already caused a cemetery that was located just outside the fort to be lost to the sea.

But excavations by the University of Aberdeen’s Northern Picts project have unearthed many exciting discoveries since 2015, including decorated bone pins and combs, and even salmon vertebrae that appear to have been chewed.

In 2022, experts and volunteers working with the project managed to dig down to the base of the upper citadel rampart, unearthing a wall almost three metres high with surviving burnt timber beams, giving a sense of the scale and importance of this site and how much still lies beneath the surface.

Explore Burghead Visitor Centre during the spring, summer and autumn months to learn more about the fort.

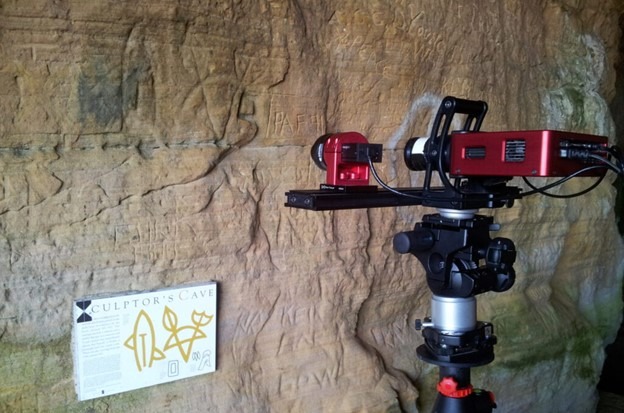

Sculptor’s Cave Symbols

The Covesea (pronounced Cow-see) Caves are a series of sandstone caves on the south shore of the Moray Firth, between Burghead and Lossiemouth. The best known is the Sculptor’s Cave, which takes its name from the Pictish carvings on its entrance walls.

The Sculptor’s Cave has been used for a variety of purposes for thousands of years, from funerary rites in the Bronze Age and Iron Age over 2,500 years ago, to a possible store for smuggler’s loot in the 17th century AD.

First recorded in the mid-19thcentury, the site is home to seven groups of carved Pictish symbols, including fish, crescent and V-rod, disc and rectangle (‘mirror case’), flower, and mirror types. The carvings have been digitised so that anyone can explore them from home.

While these are classic Pictish symbols seen across the country, their placement is unusual; most Pictish symbols are found on standing stones and not inside caves (with the notable exception of Wemyss Caves in Fife). This collection from Covesea had been dated to the 6th or 7th century AD (around 1,300 to 1,500 years ago), but recent research has questioned this dating which has led to interesting theories about what these symbols could mean and why they were carved.

Sueno’s Stone

Standing about seven metres tall, Sueno’s Stone near Forres is covered top to bottom in carvings. The stone is thought to have been decorated in the 9th or 10th century AD, and unlike many early medieval carved stones, is believed to still be in the same spot where it was first erected. It was probably designed to be a landmark, visible from a great distance.

The two faces of the stone show very different images, but it’s likely that their stories are linked. One side shows a Christian cross above a royal inauguration (crowning ceremony) which is unique in Pictish and early medieval Scottish art. The other shows a grisly battle scene with numerous beheadings.

We can’t know for certain what story the stone is telling, or if the scenes which are depicted actually happened. However, some scholars suggest it may relate to events in the mid-800s AD, when Gaelic-speaking kings seem to have risen to power within Pictland. It was a time of great upheaval, with the country under pressure from raiding Scandinavians.

Scholars continue to interpret the scenes on the stone and have even connected them to other Pictish sites in the area.

A Pictish Religious Centre at Kinneddar

In the medieval period, Kinneddar near Lossiemouth was the centre of the bishopric of Moray, but its significance likely stretches back even further into Scotland’s past.

The settlement is thought to have been one of the major ecclesiastical sites of northern Pictland, in use from the 7th century through to the 12th century AD when Kinneddar first appears in the historical records.

From 2015-17, research was carried out by the Northern Picts project, as well as through development-led fieldwork by AOC Archaeology. Surveys produced by both teams identified traces of vallum enclosures (ditches or banks enclosing the sacred area of major ecclesiastical centres) around the modern graveyard and nearby – the largest such enclosure complex yet identified in Pictland.

The excavation that followed also uncovered some of Moray’s first evidence of early medieval ironworking which added to our understanding of the organisation and development of the practice in this area. Radiocarbon dates indicate that the overall activity at Kinneddar probably began in AD 585–655 and that the vallum ditches probably date to a few hundred years later in the 7th or 8th century AD.

The evidence from Kinneddar suggests that this location once housed a major ecclesiastical centre of Northern Pictland that was established by the 7th century, and the excavations suggest that important information on what activities occurred there are still preserved beneath the ground.

If you want to see a range of Pictish artefacts all in one place? Elgin Museum is home to a significant collection of carved stones, including examples from Kinneddar and Burghead, a fragmentary brooch-pin found through metal-detecting at Birnie, and much more.

The Museum is open during the spring, summer and autumn months (see their website for updates on opening times) but it is possible for individuals/groups to visit by appointment during the winter if they contact the museum in advance.

This article was written by Dig It! Find out more their amazing work discovering Scotland’s Hidden Stories.